David Baker is a man you cannot miss -- and surely cannot forget.

Baker -- once called the "New Tower of Power" by Sports Business Journal -- lumbers down a hotel hallway in Houston on a Saturday in February with a message and camera crew in tow. The message doesn't come on a scroll or written memo, but through a knock on a door.

Much has been made of Baker's knock, delivered with a forcefulness that fits the man creating the sound -- Jason Taylor has likened it to getting a knock from the FBI. But it does not herald bad news. Instead, it summons football immortality.

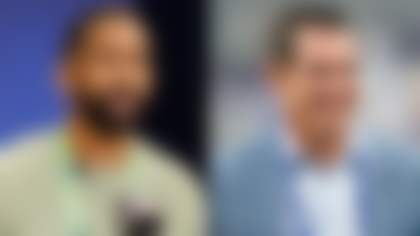

As his knock this afternoon is answered, the room, brimming with nearly 20 of those closest to Dallas Cowboys owner Jerry Jones, erupts in cheers. The video shows tears flowing and the people inside embracing as Baker informs Jones of his impending enshrinement into football's most hallowed club.

Baker is the president of the Pro Football Hall of Fame. The 64-year-old's frame -- all 6-foot-9 and nearly 400 pounds of it -- looms over almost anyone. His suit size is a 64. When Baker is approached for a handshake, the hand that isn't his is guaranteed to disappear within his massive paw.

While his physical presence is robust, his delivery is gentler. To Baker, his youngest son is "Sammy," his wife is "sweetheart" and the Pro Football Hall of Fame is "the most inspiring place on earth."

There's an inherent irony in the fact that the man who leads the sacred home of football immortality never played the game. Baker says he was "literally too big to play football," instead gravitating toward basketball, which enabled him to attend college at the University of California-Irvine on scholarship as a power forward (he still holds the school's all-time rebound record and is third on the all-time scoring list), play professional basketball in Europe and, later, attend law school at Pepperdine University.

Baker's lack of on-field experience didn't keep football from sucking him in. His passion for the game -- which he considers to be "the greatest sport ever devised" -- drips from his every word as he talks about the mission of the Hall of Fame: honor the heroes of the game, preserve its history, promote its values and celebrate excellence everywhere.

It's not marketing copy, either. Baker is quick to explain that his purpose is greater than any he's had in his life.

Baker was raised in Downey, California, near Los Angeles, by two parents who, he says, couldn't read. His father, Carl, worked for 32 years in a lumberyard. His mother, Beuna, who was named by a census-taker because she didn't have a name, became a caregiver for foster children.

Baker recalls an image of his father, slumped in a chair after a long day at the yard. If David asked if he was all right, Carl would sigh, pause, and say, "Moved a lot of lumber today."

The lumber Baker has moved throughout his life has come in many different shapes and sizes. First, it was actual lumber, moved while working alongside his father on his off days as a teen, leaving his hands sore for weeks. Baker was once a city councilman and later became mayor of Irvine, California, to which he still proudly refers to as one of America's first master-plan cities. But a decision in 1988 cast him out of politics entirely.

While attempting to win the Republican nomination for a Congressional seat, Baker forged a $48,000 check. He stopped payment on the check soon after, pleaded guilty to the charge of forging the check and was later sentenced to community service. It cost Baker not only his job, but also his marriage of 13 years.

"I wouldn't want to go through and hurt anybody, but I also would say that I probably wouldn't go back and change it for what I learned," Baker says.

Baker rarely misses a teachable moment. An English Literature major while at UC-Irvine, he has a quote for every situation. When coaching his sons in basketball during their younger days, Baker would often halt action in the middle of practice, have his players sit down on the court and listen as he taught a 30-second lesson.

Baker's learned lesson came in handy when he entered the AFL with his purchase of the league's Anaheim Piranhas in 1995 amid plenty of in-house turmoil. The league was struggling to retain leadership at its highest level, exhausting three commissioners in its first 10 years of existence. Baker's first meeting between owners in 1996 left him second-guessing his acquisition.

"Guys were screaming and yelling at each other and threatening lawsuits, and I thought, 'Oh my God, what did I get myself into?' " Baker recalls. "I found out that each of the three previous commissioners had been punched out at some point, and there were like six votes on dismissing the commissioner."

Fourteen months later, Baker so impressed the other owners by calling for honesty at yet another contentious meeting, as detailed in a Sports Illustrated profile, that he was made chairman of the board. Baker says the other owners "had such a distrust of each other, that they'd rather take a chance on the new guy than trust one of them."

A year after that, Baker took the place of departed commissioner Jim Drucker, a role Baker thought he'd fill "for a year." But Baker went to work on growing the league. A constant thinker, he'd stay up late into the night while living in an Upper East Side apartment in New York City, scribbling his wild ideas on a yellow legal pad, creating stacks of the sheets he'd leave outside the bedroom door of his eldest son, Ben, for Ben to type up when he woke.

Baker oversaw massive growth for the league, including television deals with NBC and, later, ESPN (which involved a Monday night slot), the sale of a team for nearly $20 million and even production of a league-licensed video game.

Baker didn't go it alone, establishing a relationship with then-NFL Commissioner Paul Tagliabue. In a meeting with Tagliabue, Baker was introduced to "a guy who had a long title" who turned out to be future Commissioner Roger Goodell. The two started going to dinner together once a month for the next decade, exchanging ideas while Goodell eyed a future role atop the NFL.

The effect of these meetings was evident to one AFL owner, who also happened to own one of the NFL's most popular franchises.

"I saw his appreciation for the game," says Dallas Cowboys owner Jerry Jones, who also owned the AFL's Dallas Desperados. "I saw his ability -- which is exceptional -- to articulate and represent an entire league. I actually thought that he could be a potential NFL commissioner."

But Baker says conflicts of interest arose as Baker's son, Sam, was drafted by the Falcons, a team owned by Arthur Blank, who also owned an AFL team. Sam's newfound wealth "scared the heck out of" Baker, who chose to leave the AFL to better direct his son -- perhaps with prescience, as the AFL soon went on hiatus as a result of the crippling 2008 recession.

Baker's guidance of his sons started well before Sam's entry into the NFL. Derailed by his ugly exit from politics at 35, Baker spent the following years on a new track, focusing on his career as an attorney in the healthcare development industry in Southern California and raising Ben and Sam. He drew up contracts with his kids that committed them to attending practices and being punctual, with pay scales for achievements in the classroom and on the court. He even had them submit invoices for allowances.

"I could be misremembering all of this, but I'm pretty sure assists and rebounds, you got more money than you did points," Ben Baker recalls. "You got like, 10 cents a point in basketball, but a rebound was a quarter, assist was 50 cents or something, because that was more important than scoring points."

That method benefits both of them today. Ben cut his teeth with the AFL's league development and broadcasting departments, spent time at ESPN and now works as NASCAR's senior director of broadcasting.

Sam played at the University of Southern California and was selected as a first-team All-American three times (2005-07) before being chosen in the first round of the 2008 NFL Draft by Atlanta. He played seven seasons with the Falcons, until knee issues (including a torn patellar tendon) forced his retirement in 2015. His dad has a large framed photo of Sam blocking for quarterback Matt Ryan in his Canton office, and jokes he still managed to find a way to get Sam into the Hall.

While Baker was engrossed in his work and kids for much of his life, he was neglecting another part of it. By the early 1990s, he was done with dating. What fortune, then, that he knew a secretary who would stop at nothing to set him up with a friend of hers who also had two children, and who was also ready to throw in the towel on romance.

The matchmaker badgered her friend, Colleen, relentlessly trying to introduce her to Baker, going as far as giving him Colleen's number and asking Colleen, "Sweetie, if David Baker calls, will you be nice to him?"

"I thought, 'You are ridiculous!' " Colleen says. "'I cannot believe you gave this man my phone number!' "

Colleen did Baker the courtesy of being cordial over the phone -- and, to her surprise, she talked with him for nearly an hour. Concerned with Colleen's comfort, Baker proposed meeting at a nearby Mexican restaurant.

There was the classic problem of the blind date, though: How would Colleen know who Baker was?

"He said, 'I'll be the only linebacker to walk in the room,' and I thought, 'What does that mean?' " Colleen says. "He walked in the room, and I went, 'Holy schnikes, that's what a linebacker looks like.' "

Colleen was so nervous, she couldn't eat her meal. No worries -- Baker ate his dish, then cleaned her plate, as well.

While he wasn't shy at the dinner table, Baker waited six months to kiss Colleen. The cautious strategy proved to be the right one, as the two have been married for 23 years.

Baker's departure from the AFL took him away from the game, relegating him to fan and follower of his son's professional career while heading the development of a medical center, Union Village, in Henderson, Nevada. It wasn't long before the game pulled him back into the fold.

The Pro Football Hall of Fame was looking for a new leader in 2013 after the retirement of president and executive director Stephen Perry, but Baker wasn't in the market for another fork in the road. He received an email request from a search firm to apply for the opening and respectfully declined, but not before forwarding it to Colleen.

"She called me, and about 15 minutes later, she said, 'Hey, we're going to go do this,' " Baker recounts. "And I said, 'Well sweetheart, I already told them no.' And she said, 'Well, you can call them back.' "

"I said 'This is as though somebody sat next to you and said who are you? And they came up with this job description,' " Colleen says.

Baker countered by saying the couple's involvement in the existing Union Village project was too much to leave. Plus, the two were Los Angeles County natives, and it gets cold in Ohio. Colleen wasn't having it.

"God will give you bread crumbs to lead you down a path," Colleen says. "Well, God did not give me bread crumbs. God gave me airport landing lights to Northeast Ohio."

When Baker took the reins of the Hall of Fame in 2014, it didn't take long for him to start envisioning new heights for the institution.

"When he first took the job [at the Hall of Fame], I thought to myself 'Oh, that'll be cool, at least he'll get to relax a little bit,' because even when he did Arena football, he wanted to take it to the biggest level," Sam Baker says.

The Hall's current state wouldn't be enough. Not for Baker.

Colleen says her husband's place of inspiration is on their bedroom floor, in his underwear, with candles lit, classical music playing and nothing but a pen and yellow legal pad at his disposal. The torch has been passed from Ben taking to a keyboard in New York City to Colleen typing up his magnificent ideas. This is how David Baker drew up his plan for what is now the $700 million Johnson Controls Hall of Fame Village.

"I go, 'Holy cow, how do you think of this stuff?' " Colleen Baker says. "Really, it's just very remarkable the way his mind works. That's not because I'm married to him and he's my husband. That's because of who he is, how his mind puts together a project or mission. He's very mission-driven."

Add another trade to Baker's long list of professions: salesman. His charm and humor shine through in every interaction with both strangers and some of America's most powerful people. When asked what the C in his full name -- C. David Baker -- stands for, he replies "Cowboy." (It actually stands for Carl, named after his father.) With Jones' family celebrating in Baker's hotel room in February, the jovial Baker quipped, "I really just came back because I had forgotten my billfold."

It seems as though he's only gotten better at it over time, bringing what Patriots owner Robert Kraft calls "a certain excitement and sizzle." Baker even went overseas to sell the Hall and grow the game, joining 18 living members of the Hall of Fame -- "Gold Jackets," as the Hall refers to them -- and Kraft on a trip to Israel, the second of its kind. Count Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and Pope Francis among those who received the Hall's pitch during the trip.

"Wherever [Baker] is, I've seen him in whatever environment, he's over there 7,000, 10,000 miles away, inviting people to come to the Hall of Fame and making it sound darn exciting," Kraft says. "His physical presence and salesmanship, he and his wife are genuine, nice people. I think people are attracted to that."

While construction remains far from complete -- the finalization date remains set on 2020 -- everything seems to be turning up roses for Canton and the Hall of Fame. That is, everything except the league's annual preseason opener in Canton, which in 2016 was unceremoniously canceled hours before kickoff due to a groundskeeping mistake that left the field unsafe for play.

Baker was forced to cancel the game, but he didn't have a public address announcer handle the delivery of the bad news. He instead took the microphone at midfield and explained the contest's unfortunate demise, while what Colleen calls "all of the four-letter words" rained down on him from the stands.

Colleen watched from the stadium's press box, heartbroken and distraught. Sam's friends and fellow players, past and present, watched on televisions across the nation.

"I got a million texts from different players that all said 'Hey, he did the right thing. As a player, I appreciate that. There's not many people looking out for players like that,' " Sam says.

It didn't take long for an important figure to recognize Baker's judgment, even in the face of great criticism. Baker took a private jet to meet with officials from Johnson Controls less than a week after the game's ugly outcome, and he began to give his speech explaining what he and the Hall were all about as the two sides convened to discuss a partnership.

Colleen says that Alex Molinaroli, president and CEO of Johnson Controls, "stopped him and he said, 'Listen, you don't need to tell me anything. I saw your integrity on the field last week. I saw what you stand for, I saw what this company is all about, and so we're in.' "

Johnson Controls is in to the tune of more than $100 million. And as construction continues for the foreseeable future, folks still make the pilgrimage to 2121 George Halas Drive to check off the greatest stop on the football bucket list.

They come for gridiron history but leave inspired, and with a memory they'll cherish. It's this impact that drives Baker to come to work every day, with a large name tag in the shape of the Hall's logo emblazoned with "DAVID" affixed to his lapel.

Baker raises his hand above his head to indicate where the Hall is aiming with this project, then lowers it slightly.

"We're aiming for here," he says before lowering his hand. "We might only get here."

He raises his hand again, above his head.

"But we might get here."