INDIANAPOLIS - It can't be totally written off, but the odds are stacked pretty high against the Detroit Lions taking a wide receiver with the No. 1 overall pick this year. They've been a franchise that, until landing Georgia Tech's Calvin Johnson with the second overall pick two years ago, mastered the art of misjudging wide receivers and burning a draft pick the following year to make good.

Whether it was the system they ran or the lack of talent or character of the player(s), the Lions made a habit of falling in love with the wrapping paper but not shaking the box to see if anything was inside. They are hardly the only team that missed on a wide receiver, which might be the trickiest position for NFL teams to gauge when it comes to figuring out draft prospects.

"You watch offensive linemen, defensive linemen, defensive backs ... whole game," San Francisco general manager Scot McCloughan said. "You don' watch specific plays. We do it. Everybody does it (with wide receivers). You see the big catch. You see the big plays so they push up the (draft) board. Well, they're jumping, running, everything's great. The interview is great. We can't miss. We're not going to find one in free agency. We don't have one like him. That's why decisions haven't panned out. It's not just recently. It's over the history of the draft."

Gaudy collegiate production by a wide receiver could showcase his ability, but it also could be a product of a pass-happy system played against defenses that might not boast anything close to NFL-caliber talent or proper counter-scheming. Forty-yard dash times can mask a lack of toughness over the middle or cause an otherwise ideal playmaker to drop a round in the draft because he's supposedly a step slow.

If a team misses on a wide receiver it could set back the offense almost as much as missing on a quarterback. Detroit and Jacksonville are still trying to overcome bad decisions at the positions.

If a team nails a first-round standout (Larry Fitzgerald, Roddy White), it did its job. If a standout is discovered in later (Steve Smith -- third round, Marcus Colston -- seventh), the scouting department looks brilliant.

In 2008, the crop of wide receivers had so many question marks no player was drafted in the first round. Ten were drafted in the second round, though, with Houston's Donnie Avery going 33rd overall to St. Louis. Denver's Eddie Royal (42nd selection) and Philadelphia's DeSean Jackson (49), arguably had the biggest impacts of any rookie wide receivers.

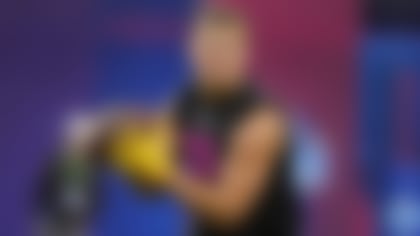

This year's class of wide receivers is considered to be pretty strong, with Texas Tech's Michael Crabtree, Missouri's Jeremy Maclin, Florida's Percy Harvin and Maryland's Darrius Hayward-Bey leading the group. There is size (Heyward-Bey, Hakeem Nicks), speed (Harvin, Maclin) and production (Crabtree). As few as two and as many as five wide receivers could be chosen in the first round.

Crabtree, the most highly regarded wide receiver in the draft, could lose some of his luster because an injured ankle is keeping him from doing most of the drills at the combine and he came up almost 2 inches short of his listed height at Texas Tech. He will try to do everything for scouts at his Pro Day in three weeks.

Crabtree comes up short

When the official combine measurements came in on Friday of the running backs, quarterbacks and wide receivers, there was one height that stood out from the rest. **More ...**

Maclin's stock could rise should he perform as well as expected at the combine this weekend. Of the top-end receiving group, he has the most big-play ability as a receiver, ball carrier and return man. He also says he boasts a "Hines Ward toughness" that coaches will regularly see on tape.

"Returning kicks, with that game-breaker ability, I am an asset," Maclin said. "That is something I can bring to the table. I also was stuck in an offense too where I had to block outside linebackers. I'm used to blocking those 245-pound linebackers that were scraping, looking to knock your head off. I'm used to it. Blocking is about heart and the ability to fight. I can tussle with any guy who comes my way."

The trait teams universally seem to be looking for most isn't so much speed, size, or route running, but ball skills and yards after the catch. With quarterbacks having to get rid of the ball so quickly now, big plays are coming more on long runs after catches made on short and intermediate routes.

"Releasing off the line of scrimmage is a big part of the initial process of evaluating receivers," Tampa Bay general manager Mark Domenik said. "The second part is at the top of the routes, the ability to separate and how they do it. Is it because they've got great feet? Is it because they know how to use their hands and create separation with their strength and size.

"The big thing, though, is the run after the catch. Not just the big plays but can he break tackles and how many does he break after the first contact?"

The YAC also is huge when it comes to this year's crop of tight ends, because most of them are receiving types. Only Oklahoma State's Brandon Pettigrew is considered a combination blocking/receiving tight end, which is why his stock is so high; he could be a top-15 selection. Others, like Southern Mississippi's Shawn Nelson, Missouri's Chase Coffman and Rice's James Casey are tight ends pretty much in name only.

They were used more in slot sets and were not routinely required to play out of a stance, head-up on a defensive lineman. More NFL teams are flexing tight ends to create matchup issues, but they would rather have combination players because specialty tight ends tip off plays and packages that can be deciphered by defensive coordinators.

"There are some tight ends that have a chance to be good from athletic standpoint," McCloughan said. "Then there are some that have never lined up at the position. They're receivers running routes. You have to ask, is he a 230-pound receiver or do you bulk him up to 250 and make him a tight end?"

More than changing the player, new Kansas City coach Todd Haley said coaches might have to start changing how they scheme to fit the personnel. Sometimes drafting a special talent -- that might be a receiving tight end -- and crafting things around that player's skills is better than trying to make a player something he's not.

Of the teams at the top part of the draft, Seattle, which has the No. 4 pick, is in the greatest need of a wide receiver, but it could settle that issue in free agency if it goes that route at all. Oakland (No. 7) and Jacksonville (No. 8) also could use an upgrade at wide receiver but they may have more pressing needs.

The teams most in need of wide receiver help are at the tail end of the first round (Tennessee, Philadelphia, Miami and the New York Giants). Much of what the Giants do at the position could be predicated on the return of Plaxico Burress, who was suspended and lost for the end of the season because of a self-inflicted gunshot wound and must contend with gun-related legal issues as a result.

Coach Tom Coughlin said Friday the Giants have to have a backup plan at the position whether Burress is part of the plan or not. As far as tight ends, Buffalo, Atlanta and New England would like to add one to provide additional receiving options.

While the spread offense that is being used more and more in college has added to the guesswork of the evaluation of some positions, there seems to be fairly consistent opinions that it helps in pegging wide receivers.

"They're out in space and they are able to show their stuff," Domenik said. "It's easier to get them off the line of scrimmage because you can move them around but because they play in space, you can see the speed, flexibility and if they can break tackles."

The spread, the tape, the 40 … there are so many ways to go right and go wrong when figuring out receivers. To which Crabtree might have had the best answer, although he was talking about his Pro Day workout.

"There are questions to be answered so I'm going to answer them," he said.