Five weeks ago, former Penn State linebacker Micah Parsons was preparing for the 2020 college football season and, were it not for the postponement of the Big Ten fall schedule, would have been readying for a road trip this Saturday to face Big Ten foe Indiana. Instead, he's now 2,500 miles from campus, spending his days in Santa Ana, California, as the high-profile subject of an expensive and never-before-done endeavor: training for the NFL Scouting Combine with about six months of lead time, instead of the usual six weeks.

The COVID-19 pandemic and the uncertainty it has imposed on college football has compelled many draft prospects, none a more highly regarded talent than Parsons, to opt out and begin preparing for the 2021 NFL Draft. Combine trainers, in turn, are now tasked with developing a six-month plan for opt-outs that has no blueprint.

And with millions of draft dollars at stake, there is no room for mistakes.

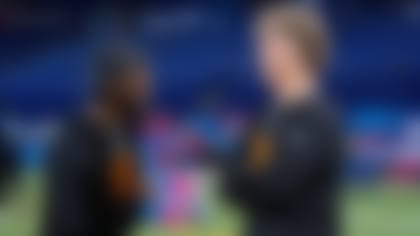

Proactive Sports Performance head trainer Ryan Capretta, who is overseeing Parsons' training along with another player who opted out, former USC defensive lineman Jay Tufele, acknowledges the obvious: Having plenty of time to train for the combine is far preferable to having too little. Nevertheless, an excess of time presents unique challenges, from preventing athletes from overtraining or mental burnout to preparing for the possibility that the date of the combine itself could be moved.

For now, the pace for Parsons is slow.

"I've never had this much free time," said Parsons in a phone interview earlier this week. "I don't know what to do with myself."

That's just fine with Capretta, whose initial work with Parsons has stayed in the realm of biomechanics, physical therapy and efficiency of movement. Combine-specific drill work will be introduced with a methodical, phased approach, and won't ramp up to a high tempo for months, probably in early December. Training on some days will be so light, Parsons will want more.

"You almost have to protect the athlete from himself," Capretta said. "Because the worst thing you can do is overtrain a guy."

Parsons figures to be one of the mostly highly rated prospects in the 2021 NFL Draft. Based on an evaluation of three 2019 game tapes, NFL.com analyst Daniel Jeremiah graded him better than all three off-the-ball linebackers selected in the first round of this year's draft (Kenneth Murray, Patrick Queen and Jordyn Brooks). Parsons announced he would opt out of the college season and enter the 2021 draft on Aug. 6. His initial plan was to stay at PSU indefinitely and work out on campus, but five days later, when the Big Ten announced it would not play a fall season due to COVID-19 concerns, he decided against it.

"I was just going to work out at Penn State and keep doing my schoolwork so I could graduate this fall, but once everything got shut down, I thought 'I need somewhere to go. I need to start getting ready,' " Parsons said.

He's set the bar high with his goals for the combine, including a 40-yard-dash time in the low 4.4-second area. Parsons said he was last clocked at Penn State with times of 4.40 and 4.44 seconds, remarkable for a player of his size (6-foot-3, 245 pounds, per school measurements).

"I haven't really had the training -- that's just what I can run off of athleticism," Parsons said. "Those times were from the spring of 2019, and I know I'm stronger and faster since then."

One of Proactive's specialties is helping prospects time their "peak" -- optimum performance in drills -- with the day they'll test at the combine, according to Athletes First's Justin Schulman, a partner at the agency that represents Parsons. Capretta's usual challenge is getting January-arriving prospects to that point just in time for the annual event in Indianapolis. However, with six months to train players who have opted out, the challenge is more about not peaking too soon.

"If the big ticket for a player is the 40, our concern is hamstrings. If you have too many reps moving at the highest velocity, you have an increased risk for injury," Capretta said. "You have to watch that you don't burn his motor, overcook him too much. And these guys are competitive to their bones. So to tell a guy you're not allowing him to run a 40, it can be a tough fight."

As for when to begin letting Parsons train at maximum exertion for combine events, the closest thing Capretta has to a model comes from previous prospects whose college teams failed to make a bowl game. Those players typically begin training in early December, a few weeks before many bowl-bound prospects start to prep. The recent trend of top prospects opting out of bowl games has added to his early December group -- Capretta noted Denver Broncos 2019 first-round pick Noah Fant and L.A. Rams 2020 second-rounder Cam Akers, as examples. Even that, however, isn't an ideal comparison because those players typically arrive with nagging injuries suffered during the season, requiring time to heal before more intense training can commence. Parsons and 2020 opt-outs, by contrast, won't have played a down this fall.

Athletes First recently struck a partnership with Proactive to train their clients exclusively at one of two California training facilities. The deal will put Capretta and his partner, Andy Campbell, in charge of training some of the draft's most high-profile prospects, and the flow of opt-outs could continue throughout the season. Capretta typically builds training schedules based on the number of days he'll have with a player before their final day at the combine, when physical testing is held. Normally, that might be a time crunch of 40 to 50 days beginning in January, after bowl season. This year, however, with the Big Ten and Pac-12 conferences exploring the option of playing seasons that could start in the winter or spring, Capretta wonders if the NFL will push back the date of the combine.

"This is all uncharted waters," said Parsons' agent, Andre Odom. "This is all unprecedented territory."

For now, Parsons' day begins at 7 a.m. with four online classes he's taking from Penn State in pursuit of a Criminology degree he's scheduled to receive in December. When classes end, he's off to a late-morning workout, followed by more schoolwork, an afternoon physical therapy appointment and a core conditioning session.

But no day is exactly the same.

New workouts will be regularly introduced. On Fridays, Parsons will be transported off-site for something different, perhaps a mountain hike, training on the beach, running hills or a yoga class. And he'll be sent home for time with family periodically, particularly around holidays.

"We can't have him feeling like it's Groundhog Day for five months," Capretta said.