Junior Seau's suicide is troubling NFL players.

No one knows precisely why the 43-year-old Seau shot himself in the chest at his oceanfront home May 2, less than 2 1/2 years after the end of his Pro Bowl career as a linebacker. What is clear - and cause for concern among other players - is that he reached some serious depths of despair.

"To see a guy like that, in such a dark place, to take the action he did ... makes you think about life after football and what it's like, and what you'll be going through, when that time comes, mentally," said Colts linebacker A.J. Edds, who is entering his second NFL season. "This might have been what people needed to open their eyes a little bit about what might happen down the road. How do you go forward to prevent it? Hopefully some good can be found from a horrible situation. Hopefully that's one silver lining - that it might help other guys keep from getting to a place like that."

In 40 interviews with The Associated Press during the last two weeks, many players voiced growing worry about the physical and emotional toll professional football takes. Seau's suicide resonated among the 13 rookies, 17 active veterans and 10 retirees, with more than half of each group saying it pushed them to consider their future in the sport or the difficulties of adjusting to post-NFL life.

It's one thing to read about hundreds of guys they've never heard of suing the league because of neurological problems traced to a career long ago. It's quite another to find out about Seau, a charismatic, recent star for the Chargers, Dolphins and Patriots who played in the Super Bowl.

"The difference with Junior for many folks my age or younger is that I played against Junior a bunch. He was a peer. It's more impactful. Not to suggest I had a great friendship with Junior or knew him off the field. I didn't. It's simply closer to home for me than a guy who played in the 70s or80s," said Pete Kendall, a starting offensive lineman from 1996-2008 for the Seahawks, Cardinals, Jets and Redskins. "All of those kinds of situations are horrible, but Junior's situation probably would have people re-examining things."

Indeed it did.

Even less-experienced NFL players in their mid-20s were forced to face some complicated questions in recent weeks.

"You can't avoid thinking about how the game might be affecting your future. Even something as small as forgetting where I put my keys. I know everyone does that from time to time, but am I forgetful because of football? Have I already done damage to my brain playing the game?" Packers tight end Tom Crabtree, who's played two seasons in the league, wrote in an email.

"When you see a guy we all assume to be so happy and successful take his own life, it's disturbing. I worry about how happy I am with life right now and wonder if the damage is too much to overcome. ... It's like these brain injuries really turn you into another person," Crabtree wrote. "It slowly chops away at your happiness. Nothing you can do about it."

He was one of a dozen players who, unprompted, mentioned brain disease or concussions in connection with Seau, even though there has been no evidence of either with the linebacker, who played from 1990 to 2009.

"The obvious questions arise: Was it depression? Brain damage? I've been reading a lot of different articles about it. I personally believe that concussions will definitely give you some sort of brain damage. Was that the cause? We won't know for sure until they examine his brain," former Chargers, Dolphins and Vikings receiver Greg Camarillo said. "But it definitely makes you think, as someone who has played this sport, about the damage that can be caused."

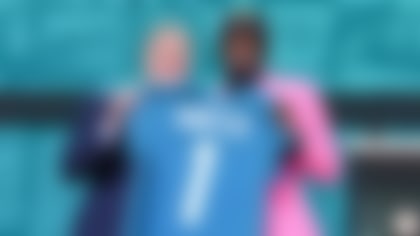

Explained rookie receiver Mohamed Sanu, chosen by the Bengals in the third round of April's draft: "You kind of wonder about your safety and your health and wonder if you'll be like that one day."

Players frequently mentioned that Seau's suicide prompted heartfelt conversations with spouses or close pals.

"As soon as something like that happens, you start calling all your friends to make sure they're OK, just checking on everybody," said Ken Norton Jr., who retired in 2000 after 13 seasons as a linebacker for the Cowboys and 49ers and now coaches that position with the Seahawks. "It just opens your eyes and makes you more aware of what each other is going through - and ask that extra question, give that extra hug, to make sure there aren't any problems we don't know about."

"`I just want to tell you if you're ever down, you're ever depressed, just call me.' He was worried. ... My buddy from Iowa calling hit home a little bit," Bowen said. "A little doubt creeps into the back of my mind: Well, maybe this could happen to me."

In responding to the AP's questions, rookies were, to a man, certain the league is making things as safe as possible for them. They, of course, have yet to participate in their first training camp or game.

But players who've spent time in the NFL were split on whether they're properly equipped for what might await down the road. Asked whether the league is doing all it can to take care of players' financial, mental, physical and neurological health, particularly when it comes to having a good life in retirement, 13 veterans or retirees said yes, while 11 said no.

"You might think you've got it bad in football, because it can be a grind and you might think meetings are a drag, but the real world gives you a totally different mindset," said Kitna, now teaching algebra and coaching football at the high school he attended in Tacoma, Wash. "There are a lot of programs available, but you have to search for the answers. That's harder for athletes, because they've been given answers their whole life."

Said Bowen: "I understand players who say, `They just throw you out the back door.' ... I would love to have guaranteed insurance. I think every NFL player would. It'd make life a lot easier. I'm 35, I have aches and pains. What am I going to be like at 45? I can't tell you that."

As for money matters, Steelers linebacker LaMarr Woodley, who's heading into his sixth season, said: "I wouldn't say the NFL takes care of players financially for the future. The NFL makes sure this is a drug-free league. You can't use steroids or street drugs; they're testing every week for that. But in terms of taking care of your finances, it's not something they push every week like they do with drugs. There's not a push that makes it mandatory for players to learn how to manage their money, or to set up life insurance or 401Ks."

The two men in charge of post-career programs at the NFL and the NFL Players Association readily admit there is room for improvement.

"Do I think enough is being done? A lot is being done. Can we do more? Yes," said NFL Vice President of Player Engagement Troy Vincent, a former defensive back in the league.

But he also put the onus on players for not participating in what's available.

"We can continue to expand our offerings, but if the athlete doesn't engage, it does no good," Vincent said. "What other employer provides this kind of service for their employee? It doesn't exist."

NFLPA Senior Director of Former Player Services Nolan Harrison said the union has been working for years to develop a new "life cycle program" to address various needs during careers in the NFL, from start to finish - and beyond.

Asked if there's a specific gap that can be improved, Harrison said: "Every area needs help."

"They need help with the identity of leaving the game: You're no longer a football player.' They need help understanding they weren't everjust a football player.' They were more than that. They weren't `just No. 74,"' said Harrison, who played defensive line. "We need them to understand they can take advantage of mental-care specialists while they're playing."

Only one veteran or former player the AP interviewed acknowledged having taken advantage of counseling provided by his team.

Three said they weren't aware such help exists.

"I could get a phone call and, in 30 seconds, my career's over. And where do you go from there? You're stuck. It's like, `What do I do next?' ... So you see a lot of players do fall into depression, gambling and partying and things like that to try to get over what happened," said Bills linebacker Kirk Morrison, who's entering his eighth season. "I think that's another time where players would seek help. But we're not built that way. ... We're not built to express our feelings."

Several players echoed Camarillo's observation that the biggest difficulty might very well be persuading players that there's nothing wrong with seeking help.

"It's a matter of a culture change, moreso than just creating a program. It needs to be something that's not looked down upon. If a player goes for counseling: `What's wrong with that guy? Why can't he deal with it?' The NFL and NFLPA can definitely help more, but it also needs to be a culture change," said Camarillo, who holds out hope of continuing his playing career.

"It's just the `tough guy' mentality," Camarillo said. "We're taught to deal with any type of weakness and fight through it. In the physical world, that works fine with a sprained ankle or something like that. But in the emotional world, it just doesn't work the same."

AP Sports Writers Tim Booth, Josh Dubow, Chris Jenkins, Joe Kay, Jon Krawczynski, Larry Lage, Mark Long, Brett Martel, Andrew Seligman, Dave Skretta, Arnie Stapleton, Noah Trister, Teresa Walker, Dennis Waszak Jr., John Wawrow, Steven Wine and Tom Withers contributed to this report.

Howard Fendrich can be reached at http://twitter.com/HowardFendrich